He was handsome, he was affable, when he had a hundred dollars he felt like he had a thousand. When he had a thousand he felt like he had a million. He was always certain that in the very near future it was all going to work out great. It almost never did. But he was always a fascinating guy to have as an older brother.

Because Quillin, starting with his very name, no middle name, was different.

It was my sister Jan, a conduit of all sorts of interesting information in my youngest days, who told me all the way back on Armstrong, that Quillin had a different Daddy than the one we knew. I once asked Mom, “What was he like, his dad?” She thought a moment and said, “Quillin is a carbon copy of his Dad, both inside and out.” It would make an enormous difference in his life and it could and would explain certain things.

When grown Quillin tracked him down, his biological dad, a man named Ford, and convinced his progenitor to meet him at the Los Angeles airport. When he walked toward him Quillin said, “He looked just like me. It was like meeting myself.” The first words out the man’s mouth were, “Kid, I don’t need this.” They spent maybe a half an hour together.

Quillin told me he came back from that trip and put his arms around Dad and told him that he loved him, and that Dad, James L., was his real Dad. Which was true. He was a Porter. But he was also a little bit different, and oh, what a character.

When we were young and went camping, you best believe he met every young woman in that campground. There was the time when a whole gaggle of girls taught Quillin to water ski in the frigid waters of a lake in the Rocky Mountains. His brothers and sisters stood on shore, laughing when he fell, cheering when he held his balance and skied.

An indelible image of that day, besides Scott laughing so hard he lost his balance and nearly fell into the lake, giving Grandpa Porter an attack of laughter that made him wheeze, was the crowd of adoring girls, wrapping Quillin up in blankets as he emerged from the freezing water, triumphant.

Then there was the trip to California, driving there in a white Chrysler station wagon pulling a green trailer. It was the trip where the camera got left on the kitchen table, which is a shame because it might have recorded an astonishing event.

On that trip our brother Quillin met and fell in love with, and more importantly she fell in love with him, Hayley Mills. She was a movie star of the time, young, blonde, beautiful and famous. How she lost her heart to a young man from Kansas, only in California a few days, how he slipped away from his parents, how he swept her off her feet, in San Diego of all places, well, it is truly a shame a camera was not around.

Hayley was so smitten with Quillin she wrote him letters and signed her name a special way, a way she only did for ones she truly loved. I know all this because my sister Jan told me. Quillin showed her the letters. He never showed me the letters. So I had to scrounge through his desk for weeks, reading all his love letters, sent to him by all sorts of women in Kansas, Colorado and other places, but I was looking for that one letter from Hayley.

It was never found.

But as it turned out there were pictures. Yes, an eight by ten glossy signed “To Quillin with love, Hayley” and a second eight by ten glossy, a contact sheet with twelve pictures, one with a man’s arm around the adorable young blonde. You could not see the man, just his arm, and in our one and only passing conversation upon the subject my brother assured me, “That’s my arm.”

He was seven years older which is a lot when one is five and he is twelve, or ten and seventeen, and so forth. For awhile Quillin told me he had been a football star in college. Many a time I pored over that Emporia State yearbook, looking for his picture on the team and those great games he played. Maybe he was gone the day the pictures were taken.

There is a story that has floated around for some fifty years that Chuck Connors is our uncle. No, he isn’t and he wasn’t. We had an uncle who looked a little like Chuck Connors. But when Quillin told the story around school while in the 8th grade The Rifleman became a blood relative and ssshhhh, no one’s supposed to know this, so don’t tell anybody, so only about seven thousand people ever believed this to be true.

All of us have a dream life. Quillin was a dreamer. If he could sell you his dream then it might be true.

It was Quillin who broke the unplowed ground with Dad, and you did not bend Dad’s will easily, about playing sports on Friday nights. He threw a fit and said he was going to play football no matter what. So Dad relented, and for the first time the start of the holy day could be profaned by the playing of a game, a victory that was a benefit to each of his siblings.

Grandpa Porter took me to one of Quillin’s football games. His opinion was, “Your brother runs like a coyote.” I remember going with Dad to the stadium at WSU and watching Quillin run in a big track meet. He won his race that day and I was proud to be his brother, and was envious of the medals he wore on his letter sweater.

He was a much better athlete than any of the rest of us. The game he loved was football. In the great football games at Porterville, Jan and Whitney were on his team, Scott and Kimberly on my team. Every game he would lay a ferocious block or tackle on a certain younger brother, which would send me tumbling into a nearby wheat field.

So when he went away to college me and my team practiced. Oh, how we practiced, working on plays my older brother had taught me. Thanksgiving was the big game and it was the only game in about a hundred my team ever won. And boy did that make him mad, because Quillin loved to win. In the grudge re-match over that one victory, that was the game Scott broke his collarbone in a collision with Quillin, and for the most part the football games ended, for which I was secretly grateful.

Now I will tell you, I think Quillin was a better big brother to me than I ever was to my little brother Scott. I can catch a baseball because Quillin hit and threw them to me for hours. He let me spend a week with him in bachelor splendor in a sprawling top floor of a Victorian house in Coffeyville, giving me a copy of the book Candy, which I devoured in one day, then going out to look for me when I stayed out too late prowling the streets of a strange big city.

On a later trip to Coffeyville he lent me his brand new Buick, a company car from whatever company he was with at the time, and I drove it much too fast, the only time I ever had a car almost up to a hundred and twenty, with a pretty girl on the front seat, a girl Quillin had introduced to me only a few hours before. I was fifteen.

He was reckless and he was a lot of fun.

He was an encyclopedia salesman, a sports writer, an insurance adjuster, an advertising man, several times a hustling entrepreneur, and ended his business life as a stock broker and investment manager.

When I heard the words Quillin and stock broker in the same sentence I knew there was going to be trouble. Because our brother, the dreamer, the reckless one, always wanted to go from A to Z and never mind those pesky little steps in between like B, C or D. He wanted it now, he could dream it couldn’t he, and for as long as we knew him Quillin wanted to be rich.

A couple of times he got close. For a few months I was an eyewitness at XMG. It was a good product, a Teflon motor oil that actually seemed to work, giving a car better gas mileage. The first week I noticed the highlight of the day was lunch. Quillin and his partner would adjourn to a restaurant across the street and order two and on occasion even three rounds of double scotches. Along about the second drink the burning question would arise, “Why kind of company jet do we think we should get?”

Not being wise in the ways of business but being a wise acre, I would point out that they had not, as of that moment, sold ten thousand dollars worth of product. “Paul,” my big brother explained to me patiently, “you just don’t understand business. You need to plan for these things.”

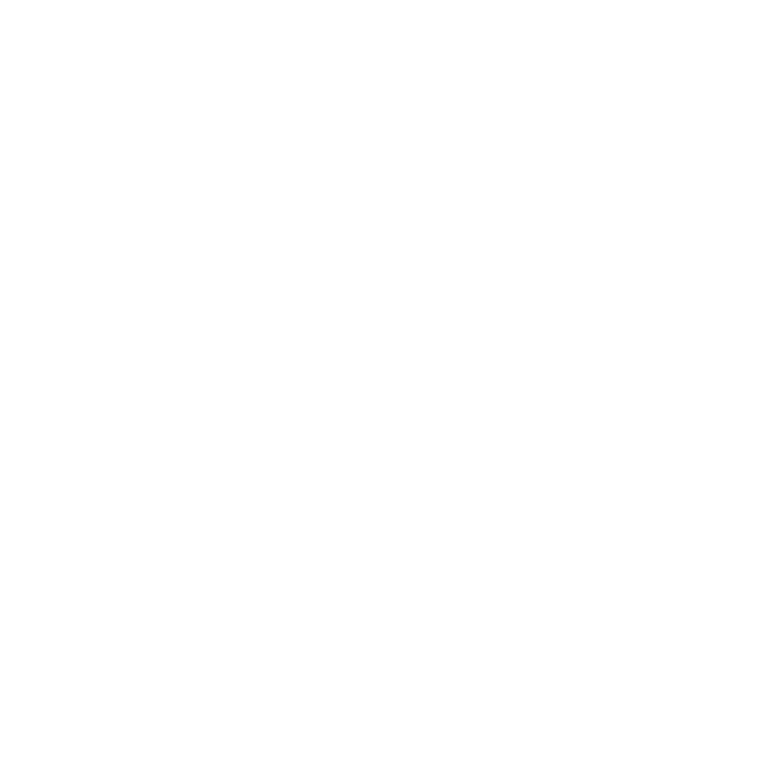

The funny thing about Quillin is that he did know great luck in his life. There was Dad, a man who adopted and loved him as his own child. There was Mom. But maybe his best luck was that he married Yolanda, who was and is beautiful in all the important ways. Together they had Lexi.

One of my memories of XMG was the day she was born. Quillin was on the other side of town when Yolanda went into labor, labor that was far too early, and he made the hour’s drive across the length of Kansas City in twenty minutes. The child born that day was no bigger than your hand and survived in part because her father loved her.

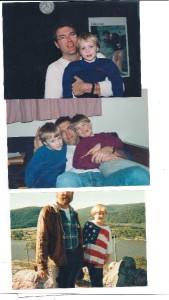

He loved all his children, Traci, Chad, Kenneth, Tiffany and Lexi. He loved you, he was proud of you, and he regretted that he did not spend more time with you. One time he said to me, “Dammit Paul, I never knew my own dad, and now my own children grow up without me.”

He knew many defeats. All of us know defeat. Few of us wind up spending ten years in prison because of one. Our brother would spend about one out of every seven days of his too short life behind bars, on parole, or on the run, events which started after he turned fifty. The man who once drove two different Lincoln Continentals, who arrived at our Father’s funeral in new Jaguar, who once gave thought to a company jet, now hid out on the Mexican border sleeping under bridges, becoming a day laborer, happy if he made enough to buy one meal a day.

He learned to speak flawless Spanish, went by foot and horseback for great distances along the Mexican border, working in cantinas as a bartender, and after being out of touch with everyone for four or five years, sneaked back into this country to see Mom.

My Mother told me, “He looked ragged, more like a migrant worker than an American.” Tired of life on the lam, of being out of touch with his family, he turned himself in and from everything I heard was relieved.

It is wrong he is gone only three years after Mom. He lived long enough to outlive jail and to know again a few years of freedom. He lived long enough to put to paper his earliest memories of Mom and tell us a story about Dad none of us ever could have guessed. He lived long enough to reconcile with his beautiful wife, with Lexi, and I hope his other children.

It was fascinating to have him as a brother. It was also too often sad.

Age plays tricks on you, so I don’t know if it was six months or two years ago that Quillin and I were on the phone. He told me that he had a hell of life and that he wouldn’t trade it for anybody else’s. I always told him if he could write the true story of his life it would be a good book, maybe a great book, and he might finally make that million dollars he always wanted. Not so long after he sent me 150 typed pages. Some parts I know to be true, some parts I know to be lies, and other parts I just don’t know.

This much is true: Quillin’s life was an adventure.

There was always something about him that made you forgive him. I knew him to be foolish, but I never knew him to be malicious. We loved him in the ways us Porters always love each other, both unreservedly and with the judgment of our own strong opinions, Christian or otherwise. Other than Mom and Dad, he affected my life more than any other single person I ever knew, a fact I did not appreciate until I began to compose these remarks. Three small examples:

Because he was a Yankee fan, I became a Dodger fan.

Because he was a business man, I became an artist.

Because he was a sports writer I began my own sports column while in high school. It was my first consistent attempt at writing.

One more story.

His first real car was a 1959 red Ford Fairlane convertible, the first in a long line of eye catching cars Quillin would drive. I shot baskets on the court at Porterville, winning the NCAA championship a remarkable number of times, and I would roll the cars off the drive to enact this miracle. One day I coasted his red convertible down the cement and the driver’s side door caught on the car next to it and was bent back double. And did my big brother yell at me for messing up his nice car?

No, he didn’t.

We are a more interesting family because he was our brother. To my remaining siblings I say no more eulogies for now. Take care of yourself and get home safely from this day when we remember Quillin, who was, as each of us are, different from all the others, though he was a little bit more so.

Thank you.

Wichita, Kansas

8 August 2010

Recent Comments